|

|

||

|

In the early morning hours of December 6, 1943 the crew of a B-24 Liberator bomber #41-28463 from the 461st Bomb Group (H) was lost between Tucson, Arizona and its base at Hammer Field in Fresno, California. There were six men aboard at the time.

In this photo can be seen the full crew complement posing in front of a different B-24, the Lucky Lee. Lots of crew photos were taken this day and all of them were in front of the same airplane. Pictured are: back row L-R, unknown, flight engineer S/Sgt. Robert Bursey*, unknown, unknown; front row L-R, navigator 2nd Lt. William Cronin*, pilot 1st Lt. Charles Willis Turvey*, unknown, co-pilot 2nd Lt. Robert M. Hester*. Also on board was radio operator S/Sgt. Howard Wandtke* and bombardier 2nd Lt. Ellis Homer Fish*. Gunners from the B-24 were not on this mission. [* = killed that day]. Later that morning, a squadron of nine or ten B-24s left Hammer Field to find the missing plane and crew. Fifteen minutes after taking off, the last plane in this formation, known as the "Exterminator," developed trouble and the pilot, Capt. William Howard Union Darden, ordered his crew to bail out. Only two of the eight-man crew made it out of the stricken plane before it crashed and sank from sight into Huntington Lake reservoir. The two survivors were co-pilot 2nd Lt. Culos Marion Settle and radioman, S/Sgt George Barulic. The remaining crew [Lt Samuel Schlosser, Sgt Richard "Dick" Mayo, Sgt Franklin C. Nyswonger, Sgt Richard Lee Spangle, and Sgt Donald Vanderplasche [or Vander Plasche] perished.

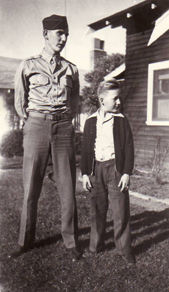

{left} Richard Spangle and his brother Tom, late 1943. Courtesy of Tom Spangle. {right} William Darden, 1940 graduation photo from Virginia Military Institute [VMI]. The following text comes from chapter 15 in my latest book "They Weren't the Only Ones." In 1943, the B-24E "Liberator" was not as current in armaments and other technology as later versions of the aircraft. This led to its primary use as a training aircraft such as the B-24E 41-28463 piloted by 2nd Lt. Charles Turvey. This airplane disappeared December 5, 1943 during a night navigation training mission from Fresno’s Hammer Field to Bakersfield to Tucson and return. On board as co-pilot was 2nd Lt. Robert Hester along with a crew of four others. This is a story achingly similar to Lt. Gamber’s missing AT-7 but with a resolution that required only sixteen and a half years. With a total of 613 flight hours including 260 hours in the B-24, Lt. Turvey was well-versed with piloting the Liberator. He had 38 hours of night flying experience too, seven of which were in the previous 30 days. For 1943, Turvey could be considered a highly experienced B-24 pilot. Though the weather forecast given to Lt. Turvey mentioned a cold front moving into Northern California, no bad weather was expected along his planned route. Two weeks after the Liberator disappeared, an investigator questioned another pilot who was coming back from Arizona to Hammer Field at 3 a.m. the night Lt. Turvey and 41-28463 disappeared. 2nd Lt. John K. Specht said, "Returning from San Diego that same evening, we encountered strong winds from the northwest at 12,000 feet and we were flown about forty miles off course to the southeast." When Lt. Specht arrived at Hammer Field it was overcast with light rain at 3000 feet and a cloud deck of about 2000 to 3000 feet thick. Pilot and author, Ernest Gann, had something to say about this disparity between what forecasters foretold and what the atmosphere delivered. He called them "on-the-other-hand" people, saying they were worse than economists at protecting themselves against any eventuality. "This would be providing this was, that is, on-the-other-hand, such and such did not occur." Gann encouraged pilots to not trust weather forecasters, or to do so at risk to their lives. At 2:10 a.m., Staff Sergeant Howard Wandtke, Lt. Turvey’s radio operator, transmitted his last position report: 50 miles east of Muroc [now known as Edwards Air Force Base], flying at 18,500 feet. Their heading of 280 degrees would take them south of the Sierra Nevada before altering course to head north up the Central Valley and home. Like 2nd Lt. John K. Specht, Turvey’s crew must have encountered strong winds which blew them east, off course. Lt. Specht’s final comment to the investigator sheds some light on why one crew could be aware of these strong winds and correct for them but not the other. "The compass radio in 463 [Turvey’s B-24] was not in very good operating condition. For a celestial mission that could have been a very good reason for them to get quite a ways off the course without realizing it." Weather crossing the Sierra would have been marginal, according to the Hammer Field weather officer. "Broken cumulus clouds, bases on the mountains, tops twenty to twenty-five thousand, visibility zero-zero in the clouds and 10 miles outside of clouds, moderate icing in clouds, moderate turbulence." The father of co-pilot 2nd Lt. Robert Hester was devastated by the loss of his son. Los Angeles resident, Clinton Hester, spent the following 14 years searching the Sierra Nevada for signs of Robert’s airplane. In 1959, Hester died from a heart attack. The following summer, two USGS researchers were working in a remote section of the High Sierra, west of LeConte Canyon in Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks. They encountered airplane wreckage in an unnamed lake and along the slopes above the lake. Army investigations revealed the wreck belonged to Lt. Turvey and Lt. Robert Hester. The missing crew had been found. This lake is now known as Hester Lake. Another B-24 Liberator was lost during the search for Lt. Turvey and crew. Squadron Commander Captain William Darden lifted off in 42-7674, along with eight other B-24s, early in the morning of December 6, 1943. Experiencing high wind turbulence, Darden lost his hydraulic pressure. Seeing what looked like a snow-covered clearing, Capt. Darden gave his crew the choice of bailing out or crash-landing with him. The co-pilot and radio operator chose to jump. Capt. Darden, his airplane, and remaining crew were not seen again until 1955 when Huntington Lake reservoir was drained for repairs to the dam. It seems the "clearing" spotted by Darden was the reservoir’s nearly frozen surface. The B-24 was found resting 190 feet below the reservoir’s high water mark, the five other crew members still at their stations preserved by cold water and anaerobic conditions.

Note: Since this chapter was published I have come across new information that contradicts or corrects some of the information I presented in Final Flight. A few of these corrections are provided in the description before this chapter excerpt. Read more about the Hester Lake crew HERE. Read more about the Huntington Lake crew HERE.

|

||

|

|

||

|

| Home | History | Images & Video | Links | Media | |

||

|

| Author | Books by Peter Stekel | Contact | |

||

|

copyright 2014 by Peter Stekel |