|

|

|

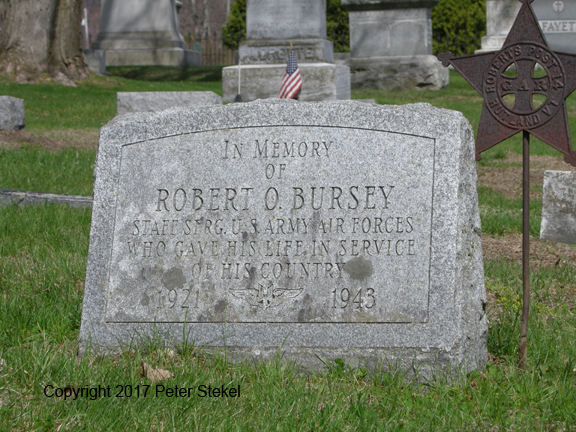

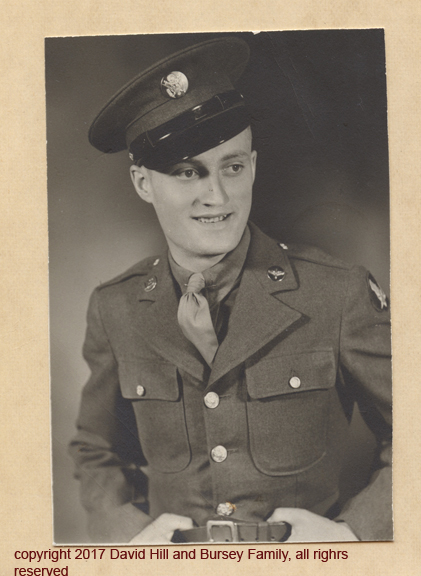

S/Sgt. Robert Oakley Bursey

(all photos unless otherwise marked are copyright 2017 and courtesy of David Hill and the Robert O. Bursey family)

|

|

Robert Oakley Bursey was born December 17, 1921 in Rutland, Vermont. His

father, William Bursey (March 1, 1876-October 6, 1937) worked on

locomotives for the railroad as a machinist. Bobís mother, Ida May Bursey

(November 15, 1882-November 9, 1969), formerly worked as a seamstress.

There were two other children besides Bob, Rena Mary (May 8, 1919-January

11, 2004) and Reta Mary, pronounced Rita, (May 8, 1919-1982). The girls

were fraternal twins. William and Ida May were married in 1917 but William

Bursey had been married once before. His first wife, Rosa Douglas Bursey

had died in 1916, at age 43, probably in childbirth. The baby, Joseph,

named for Rosaís father, was stillborn.

(Rena, Bob, and Reta - 1943) Living next door to the Bursey family in Rutland was Carroll James (CJ) Hill (July 2, 1919-November 14, 2010). He and Rena Bursey were married February 17, 1942 and had three children. David Hill, the youngest, is convinced it was his father, CJ, who inspired Bob to enlist. "Uncle Bob emulated my father because he was like a big brother Bob didnít have." Both boys were talented "shade tree" mechanics and they bonded together while working together on cars in the yard. CJ also owned and operated a filling station and Bob would hang out there. In 1942, CJ enlisted in the army and tested into the pilot program. "The story goes that Uncle Bob wanted to follow my father into the air force." Unfortunately, bad eyesight and other health issues defeated that dream. Bob Bursey never should have been on 463. Truth, awful and terrible truth be told, he should not have been in the army at all. It pretty much says so right there at the bottom of his September 12, 1942 enlistment physical: UNDERWEIGHTĖLIMITED SERVICE. It says LIMITED SERVICE not once but twice: typed and stamped. It wasnít simply that Burseyís slender 5'9" frame supported a scant 126 pounds; that was the most obvious "defect" presented in order of importance in the summary section of the physical. And it wasnít because he suffered from pes planus (flat feet) and genu varum (bowed legs). There was also a scar on his neck where Burseyís cervical lymph nodes had been removed. His vision is described as "defective." Six of his teeth were missing and two were misplaced inward or outward. Eight other of his teeth had cavities and required serious dental work to repair. A year later all the work had yet to be completed. And he smoked like a chimney. Taken all together, not a stellar physical specimen. Bobís other sister, Reta, married Richard Allen (February 7, 1920-October 13, 2003) on August 23, 1943. Bob and Dick were the best of friends and the last time any of the family saw Bob was when he returned to Rutland for the wedding. On the seventh of that month Bob had completed his course in aerial gunnery at Laredo Army Field in Texas. The timing was fortuitous for arranging a furlough - Uncle Samís graduation gift for a job well done. Once in Rutland he posed for numerous photos with everyone; there are some humorous snaps of the girls shouldering Bobís parachute.

When it was time to move on, Bob left most of his personal belongings behind in Rutland - the possessions he would have normally wanted close by. Itís almost like he had a premonition of an ill wind. The last anybody heard from Bob was a phone call to CJ, shortly before Bobís death. Something had happened and Bob Bursey was frightened half to death. He begged his friend and brother-in-law to do anything he could to get Bob out of there, to get him a transfer. Pilots were so revered in those days, it isnít too much of a stretch to see Bob thinking his brother-in-law held sway with the brass. But what could CJ do? He was a lowly first lieutenant flight instructor. What was so scary to Bob? We know from Dick Mayoís diary that by December 5, 1943, Hammer Field flight crews had been constituted for a month. They hadnít had much practical experience in the air though - at least by November 15. "We have been scheduled for eight hrs of flying every other day but due to the faulty condition of the planes we have spent most of the time on the ground." As a mechanic and flight engineer, Bob Bursey would have been fully aware of engine and aircraft conditions at Hammer Field. Perhaps it was a lack of confidence in the B-24 Liberators that had scared him so. Prior to the disappearance of 463 there had been several aircraft mishaps due to mechanical issues. Maybe this contributed to a lack of confidence. Only one letter from Bob survives and itís a love letter to his mother. The note is written on a torn piece of paper. Itís an amazing and wonderful letter for its unabashed affection and sentimentality. Darling These are the original wings that I won, so I want you to wear them my angel and please wear them well angel, because I went through hell to get them, and I am sure proud to have you wear them for me. Please keep them shined up well. God bless you all and please donít worry. Sgt Bob. xxxxx xxxxx

(Bursey family Christmas, 1942) (contemporary scene) Essentially on the same training track as Dick Mayo, judging from his enlistment date Bob would have probably received his wings, and a promotion to sergeant, in August, 1943 after finishing his aerial gunnery class. Bobís letter might sound strange to Twenty-first century ears. Especially given this was a letter from a boy to his mother. But Bobís nephew David Hill points out, "Thatís how many young men spoke to their moms." Hill also thinks it important to consider, "Bob was essentially the man of the family," since his father had died in 1937. "My grandmother was a strong-willed woman but Bob was the only male in the family. That might be why he spoke that way." Given the evidence from his enlistment physical, Bob Bursey should have been 4-F. But he wasnít. Of the tragedies to befall the boys of 463 and Exterminator, Burseyís is the most senseless of all because he shouldnít have been there. Beyond his health history, Bob was needed at home to help support his mother. Itís there on his enlistment form: unmarried with one dependent. Before his death, Ida May Burseyís husband, William, was laid low by a debilitating stroke. In a show of small-town blue-collar worker solidarity, every Monday through Friday morning until he died, Willís buddies from work would stop by the Bursey home at 140 Grove Street. They would load Will up in a wheelbarrow and roll him one mile to the railroad machine shop where they had worked together for years and years. That way Will Bursey would have something to occupy his mind, if not his body, all day. They would bring him home in the afternoon for supper, take him back to work, and then return him home every night for dinner. Economic life could be grim for single working women or widows before any old-age, survivors, or disability insurance program existed. The Railroad Retirement Board was established in 1935 and, along with Social Security, was designed to provide economic security where it had never existed before. But both programs were instituted two years before Will Burseyís death. Itís doubtful he was vested and therefore could not have left much of a legacy to his wife and children. For several years, until the children were old enough to get steady work in Depression-era rural Vermont, the Burseyís sole source of income was likely from renting out the upstairs portion of their two-story house and any sewing work Ida May could drum up. Robert Bursey graduated from Mt. St. Joseph Academy, a Catholic school in Rutland, in either February or September, 1940. Between June 13, and November 12, 1941 he was enrolled at the Frederic Duclos Barstow Memorial School in nearby Chittenden where be attained a certificate in machine shop practice after a 210 hour course of study. From there he quickly moved to a $68.00 per week job at Ford Motor Companyís Astoria, Long Island, aircraft plant, working in the Sensitive Drill Department. There, he roomed with fellow New Englanders and night-shift workers, Henry Latouche and Robert Dunbar. Foreman F. Austinat later recalled the young man as, "A conscientious worker; if Iíd had a shop full like him, thereíd be no production problem. Everybody liked him." Iím willing to bet that Ida May Bursey depended on her son for at least some of her financial obligations. After all, he was the man in the family and that sort of thing meant something in those days. Why else would Bob list her as a dependent on his enlistment papers? One sister was married with the other soon-to-be married. Mrs. Bursey would soon be on her own, without a pension, and no means of support without her son. Putting his poor physical condition together with his filial obligations leads me to the conclusion that Robert Bursey did not have to serve in the army. That he chose to follow through, none the less, indicates what a fine young man he was. Bobís nephew, David Hill, told me the family always knew that his uncleís remains were not complete. Of the boys on 463, at least Bobís remains were identifiable. This didnít make the knowledge acceptable or understandable. It tore up Bobís sister, Reta, and she never recovered from the shock. We talk a lot about closure; how important it is. And, it is. But when it comes, especially when it comes ten or more years later, itís like dealing with the death of your brother, or your son, a second time. Sure; closure is wonderful. But itís also awful. And horrible. And terrible. It not only digs up old wounds, it gouges and rips them open.

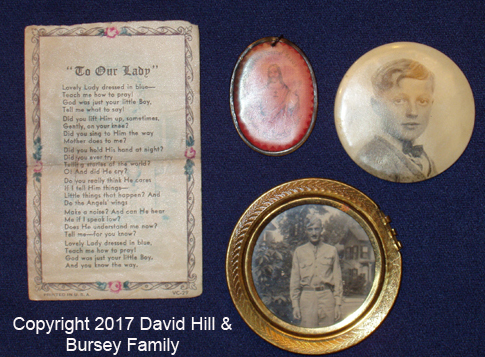

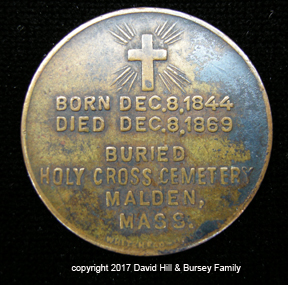

(some of Robert Bursey's affects found with his remains) The United States of America, Office of the Quartermaster General, Memorial Division, remanded Robert Oakley Burseyís earthly remains to his mother Mrs. Ida May Bursey. The remains were conveyed to the Clifford Funeral Home at 2 Washington Street, in Rutland, Vermont by Sgt. Joseph Oresik. Mrs. Bursey referred to the sergeant as, "a very fine gentleman," who she was proud to receive in her home. In appreciation of Oresikís service to this hometown boy, a thankful, grateful, and appreciative Rutland citizen presented Sgt. Oresik with the latest in 1960s technology: a television set. Robert Oakley Burseyís human remains were then committed to God and eternity in the Bursey family section of Rutlandís St. Joseph Cemetery. A Solemn Requiem Mass was conducted by the Right Reverend Monsignor Alfred L. Desautels from the Immaculate Heart of Mary Church with full military honors provided by the Air Force 380th Combat Group from Plattsburgh, New York. Bob is now at rest in St. Josephís, along with his sisters and their husbands, his father and mother.

On October 6, 1960, Mrs. Ida May Bursey, a still-grieving yet appreciative mother, wrote to Donald L. Wardle, lieutenant-Colonel with the armyís memorial division, to express her gratitude for everything the army had done to finally bring her boy home. "We will always cherish and hold in grateful remembrance your kindness, courtesy and sympathy, shown to us, in your long journey to our home. God bless you, Colonel Wardle, with a long and happy life. May God reign in our home and hearts forever."

|

| | Home | The Crews | B-24 Liberator | Media | Links | Images| |

| | The Author | Books by Peter Stekel | Press Packet | Contact | |

|

|Extended end notes from Beneath Haunted Waters|

|

|

copyright 2017 by Peter Stekel - all rights reserved |